EESA flies again

What’s new?

It’s not all bad news

- Apply for a BVLOS exemption (Beyond Visual Line Of Site). This is quite expensive and long winded process, but is our best chance of flying in the UK.

- Apply to other countries. Some countries are more open to off-the-wall applications such as ours. So far we’ve approached Iceland, Spain and Australia, and Canada and Poland are other countries we could speak to. The Scouting Association has given us permission (and insurance) to fly from, over and to any of their property worldwide, too (we’re working with a local Scouts group as part of this project).

With the weather occasionally calming down, we’ve been able to get outside and perform some more tests of our gear for Equal Experts Space Agency.

For our most recent balloon flight – our third – we sent a weather balloon up to 30,000m to release a toy glider, using the release mechanism and scripts we’ve written. Specifically, we wanted to test the following:

- The servo motors (which release the payload), to check they work at low temperature and high altitude (low pressure)

- Do our GPS and barometer reports match up? This would tell us if altitude is being reported correctly.

- Our GoPro cameras – we had two onboard, and were keen to see if they would work positioned outside of the payload box, without protection.

- Does the mission script work? Does it successfully release a toy glider at the intended altitude?

- Observe the flight of the glider at 30,000m; does it fly or plummet uncontrollably?

Incidentally, if you’re curious to know more about the scripts controlling our flights, you can view our code at the project’s Github.

Here’s how it went

The nature of this enterprise is that there’s often an unforeseen complication, and so it proved this time. When we retrieved the gear, we found the flight logs – informative data on how the flight is progressing – hadn’t been recorded during this flight. Unfortunately, the SD card they are saved to corrupted. It’s fair to say this wasn’t a helpful development!

Still, as I’ve said before, identifying and solving these issues is the point of all this, and highly satisfying (and what makes it analogous to our work for our clients!). Here’s a rundown of the rest of our findings:

Servo motors: Positive news here. We tried standard grease in one motor and silicon grease in the other, and both seemed to have worked upon landing. Reviewing our onboard footage more closely confirms that both kept working as expected.

GPS/Barometer altitude: We can’t tell if it was the barometer pressure reading or the GPS height measurement that actually triggered the glider’s release, thanks to the loss of our flight logs. But we could work out the altitude at the time of release by combining onboard black box data with video evidence of when the glider was released. It turns out this happened at 29,851.3 metres – just 15 seconds before the blackbox recorded 30km. So between them, the GPS and barometer seem to be doing their job:

GoPro camera: Our footage from the Karma camera – which was carried outside of the payload – suffered from frozen condensation on the lens. Our GoPro Session’s lens didn’t have the same problem though. This is odd – but either way, we need to try to fly when humidity is lower (another aspect of the weather that so affects this project). On a related note, the gimbal holding the camera managed to survive the speedy spinning of the descent very well indeed.

Glider performance: The glider released and fell – extremely quickly! It seemed to catch the air and do what it’s supposed to (glide) before becoming too small to see from the balloon cameras, but there was a lot of tumbling before this. We want to experiment with releasing the glider from its tail next time, to see what difference this makes; for this flight, it was released with the tail down.

Working out the stall speed at 30,000m – and therefore, how far the glider has to fall before it can even out and fly horizontally – is one of our next tasks.

A hard landing

All in all, this was a pretty successful outing for our equipment. But one last aspect we hadn’t planned for was the speedy fall of our payload once the balloon burst. The latex from the balloon seemed to become tangled with the parachute, preventing it from opening properly. This meant the descent rate was faster than predicted and the payload landed a good few miles away from where it was supposed to – in a wheat field.

It was soon spotted via our drone (permission granted, of course). Next time, we’ll need a longer line from the parachute to the balloon, to try and stop this from happening again.

It’s been a little while since I last posted an update about our EESA side project – Equal Experts Space Agency. But we’ve been very busy in the background…

In an ideal world, we’d have achieved our dream to fly our UAV in the highest ever horizontal flight by now (if you’re unfamiliar with the plan, check our dedicated page). But with a project like this there’s always something to trip you up, and amateur space flight isn’t a straightforward problem to solve. That’s why I love it!

Still, our plan remains the same, and we’re making good progress – ably abetted by the boys and girls of Addingham Scout Group, where I am also a Scout Leader. Here’s a quick summary of what we’ve been up to since our last post.

Low level flight tests

We performed lots of successful tests with our initial drone, which set out to test the GPS programming. We’ve now moved onto the bigger frame, which we’ll use for the record attempt itself. Our first go wasn’t successful as the bungie hook, used to launch the plane from the ground for low level tests, was placed too far back.

We’ve now rebuilt the frame, but have been unable to test it again thanks to a combination of trips away and unsuitable weather conditions when I have been around (perhaps this is why NASA chose Florida over Yorkshire).

Release mechanism tests

We needed to test the release mechanism repeatedly, but can’t keep sending weather balloons up each time. So we built a huge, heavy lift octocopter drone, capable of lifting the payload to 120 metres and automatically releasing it to drop (or fly) to the ground.

This has worked a treat with test payloads (and thanks go to Addingham Scouts who have tirelessly retrieved the payloads we’ve dropped everywhere, once acclimatised to the drone!). When we’ve established our big plane is capable of stable flight we’ll be launching the drone again with that attached. Again, something that’s dependent on weather conditions.

Permission to fly

Achieving our goal isn’t just a technical feat – it’s a regulatory one. We need the UK Civil Aviation Authority to be happy with what we’re up to and give us the go-ahead before attempting the record flight.

Getting permission has been the source of our biggest delays; the CAA is very busy, with staff away on holiday to add to the pressure, so has not been able to assess our applications for flight exemptions. Back in June I applied for two balloon launches to be performed in July but I’ve still not had the paperwork back. This week I’ve resent the application with the dates changed to August. This is something that’s out of our own hands, really, so we’re just focussing on being ready when the time does come.

Fancy stuff

Besides the new developments we’ve been working to add enhancements to what we already have. We’ve been testing our ‘sense and avoid’ scripts on the wilds of the Yorkshire moors. These automatically keep our equipment well clear of other planes. We have it set to 1km of horizontal separation (much further than the 500m mandatory separation), and can see our flight plan change when a commercial jet flies “near” (although the jets in question are actually 10km above our plane – we’re only testing in 2D without taking altitude into account).

We’ve also added a geofence to our tests. This restricts the plane from flying more than 500m from its take-off point, keeping it in sight all the time. If it can’t maintain a 500m horizontal separation with commercial jets it will automatically fly back to base and land.

We’re hoping that this extra safety feature will make it easier to write a CAA safety case for our eventual record attempt.

That’s it for now…

All in all then, busy times – we’re having a lot of fun solving the various challenges along the way and we’ll keep you posted! For anyone curious about the technicalities, we’re sharing information and code up on the project’s own Github.

The appearance of favourable weather conditions recently allowed team EESA to test its balloon apparatus – and we now have plenty of new data to work with (and some more problems to solve – just the way we like it).

We’ve already written about the aim of our Equal Experts Space Agency project on this blog, and you can check out the entire project on our dedicated EESA page. In short, we’re aiming to fly our drone higher than has ever been achieved.

For our latest test, we sent our balloon up with a 3kg payload to simulate the eventual drone weight). We also included the flight computer, to check it all works as planned at high altitude. Here’s some video taken from the test; as you’ll see, we are getting seriously high:

As well as being good fun, the aim of this test was to get answers to some vital questions:

Can our balloon equipment take the drone high enough?

A definite YES! The balloon reached 34,632 metres before going pop. We’d predicted 33,000m, so that’s a great result. We’re getting our equipment up to altitudes where it can potentially break records, which is great news.

The gear came down to earth within 10 miles of where we’d predicted, too, in Worksop.

Can the flight computer cope with the altitude?

No – not yet, anyway. Things were less positive here, as the GPS stopped recording at ~21km. We suspect that the GPS receiver failed when it became too cold, so we now need to repeat this same balloon test, while trying some new ways to keep the GPS receiver sufficiently warm.

We can’t progress to the next stage without confirming that the GPS will work. Without it,the plane will not know when to release from the balloon, where to fly to, or how fast it’s going.

All in all then, a mixed bag for this test – but getting the GPS to work at altitude should not be an insurmountable problem, and it’s exciting to know we are reaching such heady heights with our gear.

Stats, glorious stats

Here are a few details from the test for anyone interested in the more technical details:

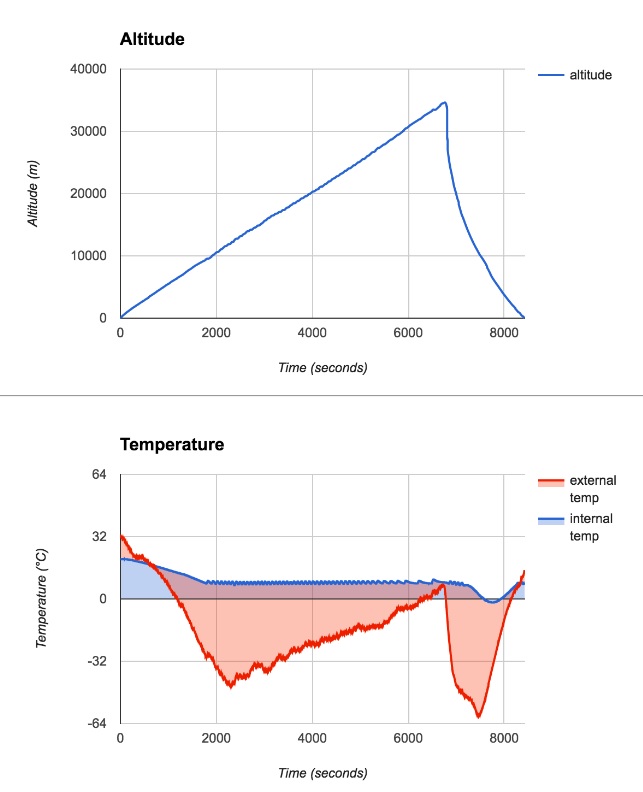

Burst altitude: 34,632m

Burst temp: 6°C

Min external temp: -63°C

Max internal temp: 21°C

Min internal temp: -2°C

Avg. internal temp: 9°C

Min temp on ascent: -53°C

Ascent rate 5.1 m/s 11.4 mph

Earlier in the year we shared news of EESA – an ambitious side project, aiming to fly an unmanned aerial vehicle higher than has ever been managed before.

EE associates Tim Squires and Nick Porthouse are the driving force behind EESA; watch this video to learn what they’re up to (and see some of the first test footage).

You can learn more about EESA on our dedicated project page. And keep an eye on this blog for news of the team’s first balloon test, coming soon.

In case you missed our recent blog, Equal Experts is supporting me in something quite dramatic – a record attempt!

I work with the boys and girls of Addingham Scout Group and we recently worked on a project to float a balloon up to the edge of space. It was a really successful experience and now EE (who I work with as a Technical Architect) is working with me to push things up a notch.

The plan is to break the record for the highest altitude in horizontal flight by a winged aircraft, and to make that happen, here’s what we plan to do:

- Our balloon will lift our unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) to 30,500 metres

- The UAV will be released and will fall. Once enough speed is reached – at around 30,000m – we aim to level it out and achieve horizontal flight.

- The UAV will circle, gradually losing altitude and heading towards the landing area (well away from any air corridor).

- The balloon will continue upwards to about 36km, at which point it will burst, allowing its onboard camera to descend.

Achieving all this will obviously take a bit of effort! We completed the first part with a successful maiden flight of our UAV.

Our maiden voyage

We won’t beat the record without testing our gear, so the main object of this exercise was simply to see how our UAV flies. We’ll be using a bigger airframe for the actual record attempt but I wanted to see how my existing drone handled the weight of the cameras (there are three onboard). You can see for yourself with the footage below:

The good news is it went really well. There was a bit of wobble but tuning the flight computer and adding some carbon rods to stiffen the wings should put that right. And the battery used only 10% of its capacity for two 3-minute flights, which is very encouraging.

Here’s a breakdown of what I was hoping to discover, and what I learned:

- Start tuning the flight computer: More tuning is needed to decrease wing wobble, increase control response and increase climb rate;

- Test the longevity of the batteries: Batteries performed well – a total of 480mAh (of 4400mAh) was used over 6 minutes flight, including take-off;

- See how it performs with the Gear 360 camera on the bottom: This was put on for the second test and handling suffered with the 360 camera, as it caused a lot of drag; things will hopefully improve with flight computer tuning;

- Landing on semi-auto flight mode: The landing was very smooth using Fly By Wire B flight mode

- Test centre of gravity: This was spot-on, even with the 360 camera on the bottom;

- Test Return to Landing mode: this also helps to establish the accuracy of the onboard GPS. It worked, but the turn home was very slow – something else that needs tuning!

All in all, then, a very satisfactory start. Our next steps:

- Make the prototype fully autonomous, including auto-landing and emergency procedures

- Build the full-size plane so that we know how much it’s going to weigh

- First balloon launch – with a box payload weighing the same as the full size plane it will eventually haul up to the stratosphere…

We’ll keep you posted!

Equal Experts is heading into the stratosphere with the launch of EESA – Equal Experts Space Agency. And no, it’s not April 1st…

One of our Associates, Tim Squires, recently made the news with his spare time project. Working with Addingham Scout Group (near Shipley, Yorkshire), he launched a balloon to the very edge of space:

For 2017, we’re supporting him in his efforts to go a step further – by breaking a World Record. Together, we’re aiming to achieve the highest ever release of an autonomous UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle), by releasing a craft from a balloon at (very) high altitude.

The record is currently set at 19,000 metres, and we’re hoping to get to around 30,000.

What on earth..?

Well, we’re actually leaving the Earth, but that’s not important right now. This might all seem a far cry from our usual activity, but in many ways it’s not at all. It’s a tough technical challenge, and we’ll be learning new skills and techniques along the way; and we’ll be doing our best to have a great time as we go along.

We’ll be featuring regular news of EESA’s progress in the run-up to our record attempt, later this spring.