Enablement as a technical practice

When you have varying levels of experience and knowledge on a team, maintaining quality should be the primary concern, to avoid errors that might impact customer value. On the other hand, we want to let developers work with as much freedom as possible, to sustain motivation and opportunities to learn. Obviously, there is no one right way to go about this, but here are the options I believe delivery teams need to consider, and the thinking behind my own preferences.

Setting the bar vs. setting a process

– which works best?

1.Setting a common bar

Here, we set a common bar to clear, with well defined expectations of what constitutes quality code; each developer is expected to meet that bar. For example, it might be the level of test coverage or the consistent use of a particular programming paradigm. The developer is given freedom over how to clear the bar that’s been set, and could choose different tools or development practices depending on their preference. The “what” is fixed (what constitutes good code) but the “how” is left up to the developer.

2.Setting the process

The other option is to set expectations around how code should be written. The team agrees a set of processes for writing software, and the limits of variation. These processes will often include pair programming and test driven development (TDD). In this case, having specified the “how”, you would then give more flexibility on the “what”.

Personally, I’d rather specify processes rather than standards when I’m working in a team with varying levels of experience. Setting the bar too high could be onerous for less experienced developers, and they’re unlikely to have enough experience to exercise appropriate choice, whereas processes can be taught, allowing developers to gain both technical and productivity skills. Processes can be agreed on a team-by-team basis, according to the levels of experience in the team.

The benefits of pair programming

It’s easy to say that two people working together are more productive than two working separately. What’s not easy is ensuring everyone on the team gets the same benefit from pairing, with experienced developers sometimes feeling frustrated at time spent coaching, versus moving tickets along the board.

While pair programming improves knowledge sharing and reduces defect rates, it’s useful to see the technique as a way to increase trust and autonomy within a team. I would potentially be wary of any one programmer striking off on their own to solve a difficult problem. But if two go together, simply by the fact of their collaboration they demonstrate that they’re following a process that is more likely to produce a high quality result. This can allow team members to operate more autonomously while maintaining alignment with the rest of the team.

How and when to use testing to further enablement

While most developers are writing tests these days, there’s still some variation over whether it’s essential to write them before the code. I still remember learning TDD and it’s not an easy process. It definitely takes some brain rewiring if you learned to code by writing simple scripts. If it’s a practice that a team chooses to prioritise, this might be an area where dedicated time needs to be allocated, to make sure everyone is comfortable with it. It’s also important to remember that there’s not just one way of doing TDD. Those of us who do it regularly have refined our practice over time; we learned by trying different things, so variation should be encouraged.

It’s good to remember that pair programming and TDD are practices that mutually reinforce each other; the cognitive load required for testing first can be better handled by two people, while the structure of TDD can provide a good template for collaboration between a pair, allowing them to take roles that focus on slightly different parts of the process, such as driver and navigator. While it’s quite a lot of work for any developer to get to the point where pair programming and TDD work together to give significant payback, it’s worth keeping it in mind as a goal for anyone in that stage of development as a programmer.

Encouraging breadth vs. depth

One more decision that you may need to make with new developers is whether to encourage them to focus on a particular area of technology, or to introduce them early to the wider range of the tools that the team uses. It’s tempting to narrow the focus to simplify the process of becoming a productive member of the team, but I would consider broadening the scope sooner rather than later, since the ability to learn new tools and languages is a key skill for a developer that is worth actively cultivating.

The more a developer knows about the range of activities on a team, the more they can start to contribute to the wider discussions of team direction. The standard advice is that people should aim to be “T-shaped”, having a good amount of breadth as well as deeper knowledge in a small number of specific areas.

Negotiating trust

We should always remember that trust is the foundation of an effective team. It’s reasonable to agree to some boundaries with developers who don’t have the breadth of knowledge to tackle every part of the codebase, but becoming a gatekeeper will quickly exhaust your time and establish a hierarchical dynamic. Getting to the point where you trust each member of the team to work productively requires negotiation, and agreed constraints should be updated frequently to recognise that less experienced developers may be progressing quickly.

Aim for parameters that are easy for everyone to apply independently of their level of experience; a constraint should be well-defined, e.g. “work in a pair when changing a database query” refers to a specific, easily identifiable part of the code. A developer can make progress within the constraint without worrying too much that they are making a mistake, then flag up early when they know they’re approaching their limits. Less explicit rules like “don’t break encapsulation” could challenge an inexperienced developer – how do they know in advance which changes could break the rule? This would be a good place to show flexibility; as long as the code works, some variation can be tolerated, with feedback and learning taking place over time.

This is far from the last word on enablement. I think there’s a need to discuss strategies and gather experiences on what has worked for other people. There isn’t a clear paved road on how to do it, so learning from each other should be a key part of enablement.

At Equal Experts, we’re frequently asked about success measures for product delivery. It can be hard to figure out what to measure – and what not to measure!

We often find ourselves working within multiple teams that share responsibility for one product. For example, an ecommerce organisation might have Equal Experts consultants embedded in a product team, a development team, and an operations team, all working on the same payments service.

When we’re asked to improve collaboration between interdependent teams, we look at long-term and short-term options. In the long-term, we advocate moving to cross-functional product delivery teams. In the short-term, we recommend establishing shared success measures for interdependent teams.

By default, we favour measuring these shared outcomes:

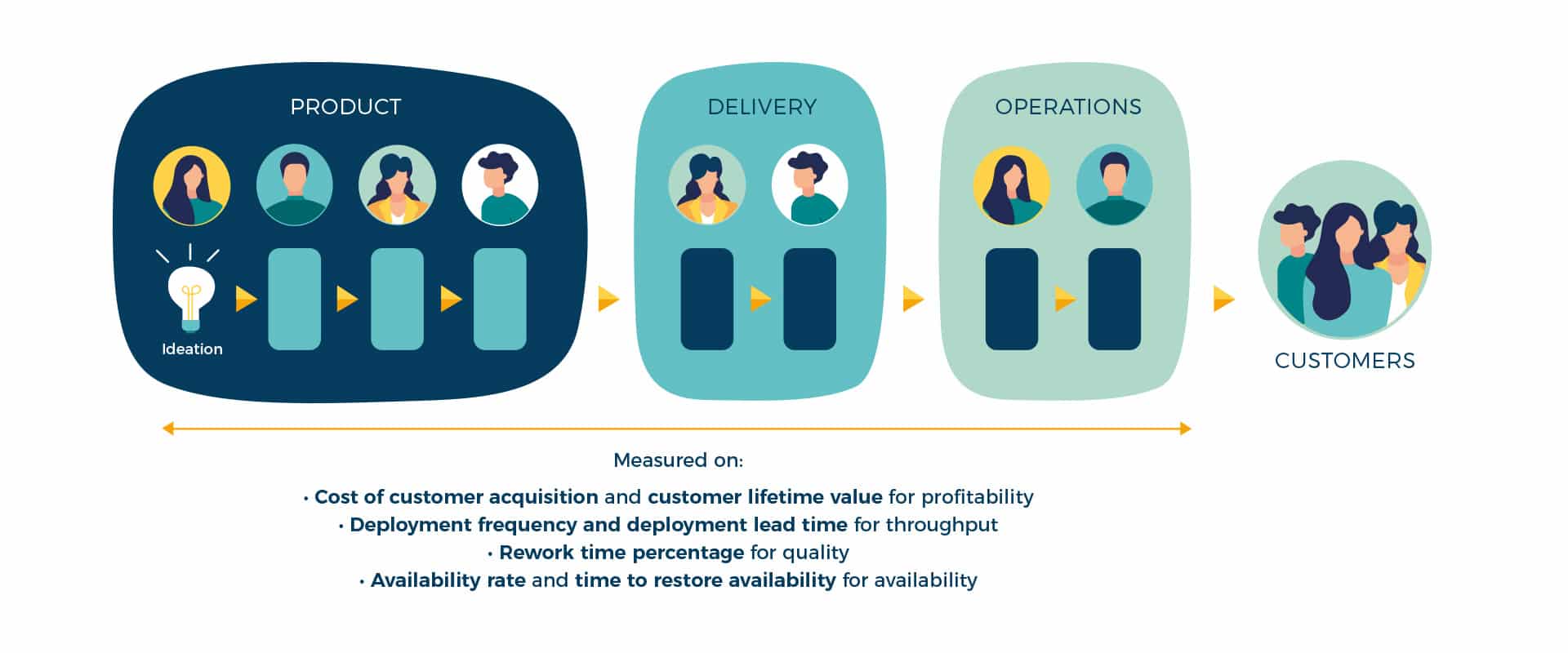

- High profitability. A low cost of customer acquisition and a high customer lifetime value.

- High throughput. A high deployment frequency and a low deployment lead time.

- High quality. A low rework time percentage.

- High availability. A high availability rate and a low time to restore availability.

If your organisation is a not-for-profit or in the public sector, we’d look at customer impact aside from profitability. Likewise, if you’re building a desktop application, we’d change the availability measures to be user installer errors and user session errors.

These measures have caveats. Quantitative data is inherently shallow, and it’s best used to pinpoint where the right conversations need to happen between and within teams. What “high” and “low” mean is specific to the context of your organisation. And it’s harder to implement these measures than something like story points or incident count – and it’s still the right thing to do.

Beware per-team incentives

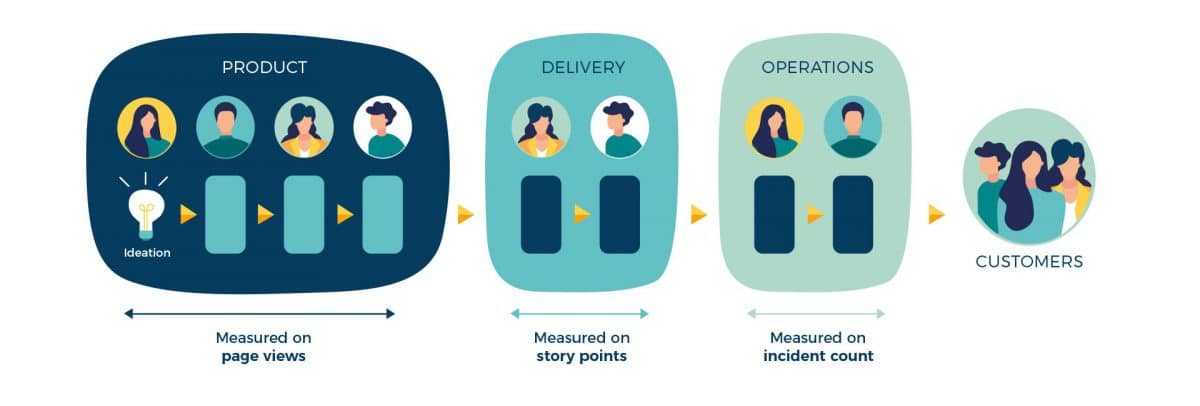

‘Tell me how you measure me and I will tell you how I will behave’ – Eli Goldratt

People behave according to how they’re measured. When interdependent teams have their own measures of success, people are incentivised to work at cross-purposes. Collaboration becomes a painful and time-consuming process, and there’s a negative impact on the flow of product features to customers.

At our ecommerce organisation, the product team wants an increase in customer page views. The delivery team wants more story points to be collected. The operations team wants a lower incident count.

This encourages the delivery team to maximise deployments thereby increasing its story points, and the operations team to minimise deployments to decrease its incident count. These conflicting behaviours don’t happen because of bad intentions. They happen because there’s no shared definition of success, so the teams have their own definitions.

Measure shared outcomes, not team outputs

All too often, teams are measured on their own outputs. Examples include story points, test coverage, defect count, incident count, and person-hours. Team outputs are poor measurement choices. They’re unrelated to customer value-add, and offer limited information. They’re vulnerable to inaccurate reporting, because they’re localised to one team. Their advantage is their ease of implementation, which contributes to their popularity.

We want to measure shared outcomes of product delivery success. Shared outcomes are tied to customers receiving value-add. They encode rich information about different activities in different teams. They have some protection against bias and inaccuracies, as they’re spread across multiple teams.

When working within multiple teams responsible for the same product, we recommend removing any per-team measures, and measuring shared outcomes instead. This aligns incentives across teams, and removes collaboration pain points. It starts with a shared definition of product delivery success.

Define what success means

When we’re looking at inter-team collaboration, we start by jointly designing with our client what delivery success looks like for the product. We consider if we’re building the right product as well as building the product right, as both are vital. We immerse ourselves in the organisational context. A for-profit ecommerce business will have a very different measure of success than a not-for-profit charity in the education sector.

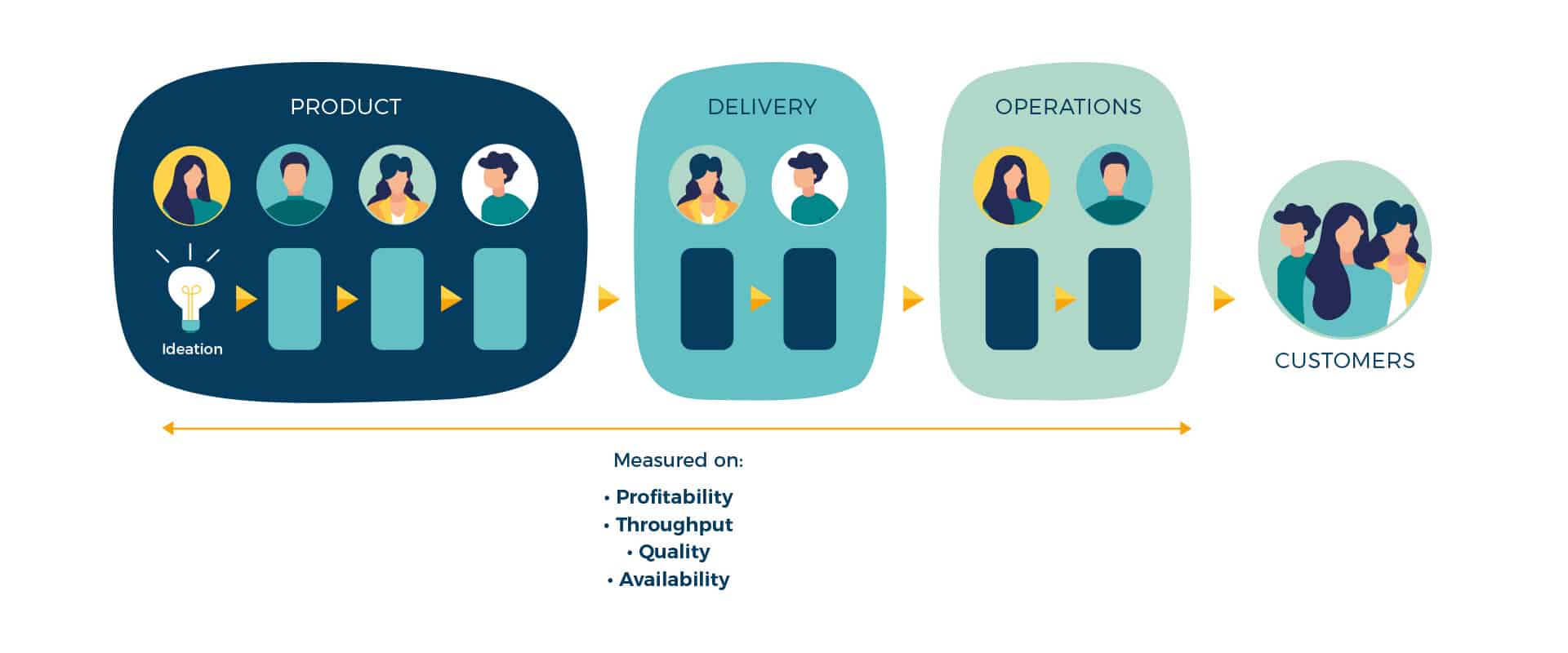

We measure an intangible like “product delivery success” with a clarification chain. In How To Measure Anything, Douglas Hubbard defines a clarification chain as a short series of connected measures representing a single concept. The default we recommend to clients is:

product delivery success includes high profitability, high throughput, high quality, and high availability

In our ecommerce organisation, this means the product team, delivery team, and operations would all share the same measures tied to one definition of product delivery success.

These are intangibles as well, so we break them down into their constituent measures.

Pick the right success measures

It’s important to track the right success measures for your product. Don’t pick too many, don’t pick too few, and don’t set impossible targets. Incrementally build towards product delivery success, and periodically reflect on your progress.

Profitability can be measured with cost of customer acquisition and customer lifetime value. Cost of customer acquisition is your sales and marketing expenses divided by your number of new customers. Customer lifetime value is the total worth of a customer while they use your products.

Throughput can be measured with deployment frequency and deployment lead time. Deployment frequency is the rate of production deployments. Deployment lead time is the days between a code commit and its consequent production deployment. These measures are based on the work of Dr. Nicole Forsgren et al in Accelerate, and a multi-year study of Continuous Delivery adoption in thousands of organisations. They can be automated.

Quality can be measured with rework time percentage. It’s the percentage of developer time spent fixing code review feedback, broken builds, test failures, live issues, etc. Quality is hard to define, yet we can link higher quality to lower levels of unplanned fix work. In Accelerate, Dr. Forsgren et al found a statistically significant relationship between Continuous Delivery and lower levels of unplanned fix work. Rework time percentage is not easily automated, and a monthly survey of developer effort estimates is a pragmatic approach.

Availability can be measured using availability rate and time to restore availability. The availability rate is the percentage of requests successfully completed by the service, and linked to an availability target such as 99.0% or 99.9%. The time to restore availability is the minutes between a lost availability target and its subsequent restoration.

In our experience, these measures give you an accurate picture of product delivery success. They align incentives for interdependent teams, and encourage people to all work in the same direction.

If your organisation is a not-for-profit or in the public sector, we’d look at customer impact aside from profitability. Likewise, if you’re building a desktop application, we’d change the availability measures to be user installer errors and user session errors.

Measuring shared outcomes rather than team outputs makes collaboration much easier for interdependent teams, and increases the chances of product delivery success. It’s also an effective way of managing delivery assurance. If you’d like some advice on how to accomplish this in your own organisation, get in touch using the form below and we’ll be delighted to help you.

In December of 2019, Equal Experts started working with ListSure, a Fintech based in Sydney, Australia. They had an incumbent technology partner but had not been able to release new features to market for over six months.

For a variety of reasons, including office limitations, access to the right talent and providing a cost-effective solution, this client engagement was established from the start with a remote-first mindset.

In our case study we discuss some of the things we did to set this up for success, including running a remote discovery through to a system migration, all whilst team members were scattered across the globe.

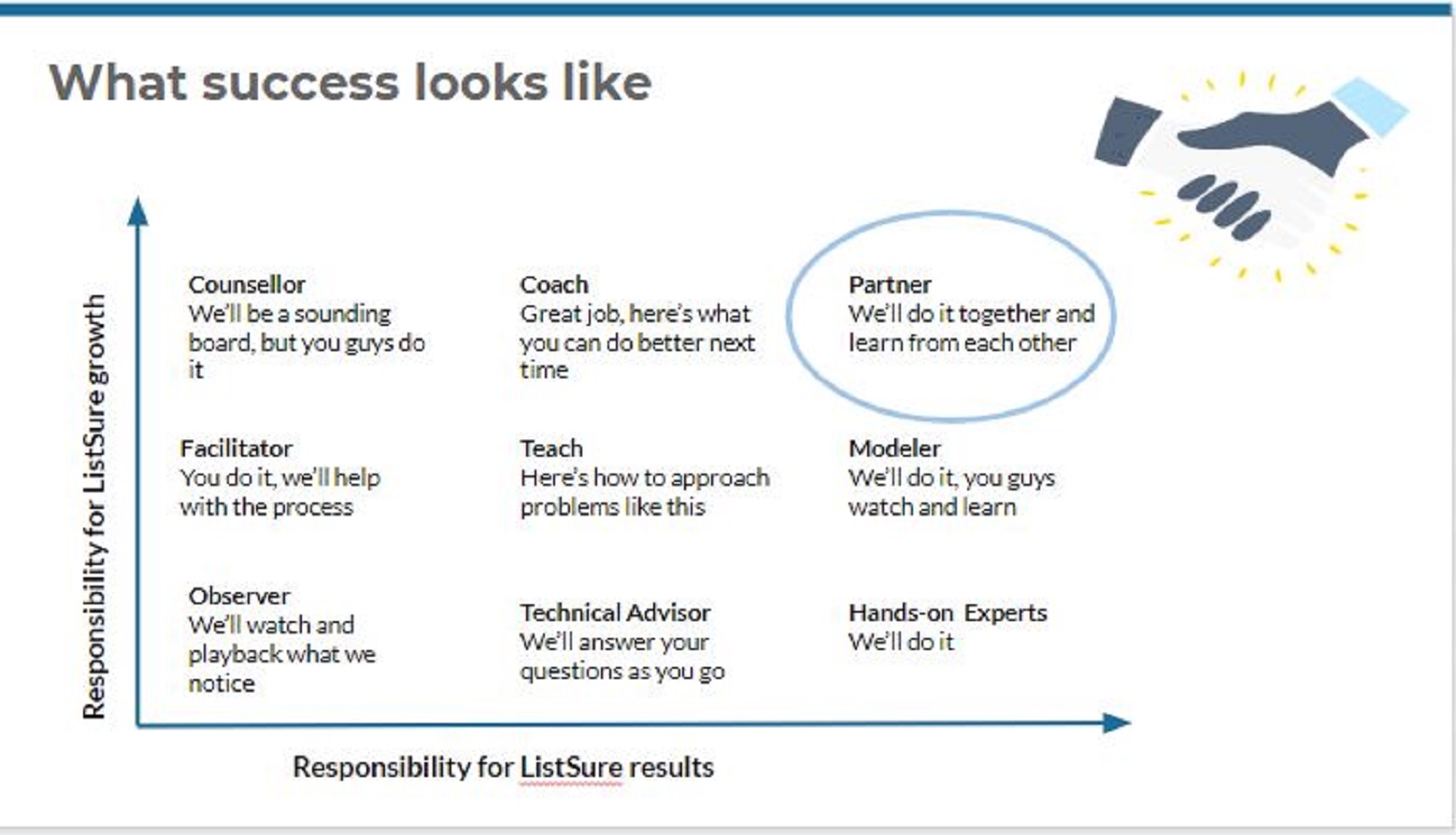

Most importantly, beyond the tools and techniques, perhaps the most essential ingredient to making this work was by taking a genuine partnership approach.

“Equal Experts have a spirit of partnership in their DNA. Fundamentally, it’s not business to business – it’s human to human, regardless of where they are located.” – Brad Melman, CEO

For more tips on remote working, please check out our Remote-Working Playbook

Last week, John Lewis & Partners announced the effective closure of their head office in Victoria, which means that a lot of staff have had to adjust to working from home.

Our experience has been that John Lewis & Partners has taken to the new remote model extremely well. For one team, the change has had a positive impact on their ability to deliver. In the first week of the change, they almost doubled their throughput and performed more releases to customers than in any other given week in the last five months.

This team considers collaboration to be their superpower. They continue feeding and watering their team spirit in the new context. There is no single correct way to do this, but here are some of the experiments the teams are trying.

Running a perpetual mass Hangouts to mimic a live office environment where you can hear each other working. Back in the office, you would be able to simply turn around to a colleague and say, “Can I chat with you for two minutes about X, Y or Z?” and that’d be fine. Not only that, but due to collocation, others could eavesdrop on the conversation even if they were not directly involved. The team has emulated that by occasionally having meets on Hangouts and keeping Hangouts always on. This helps the team feel in touch with each other, and conversations can spontaneously spring up. Even though these meetings don’t necessarily involve everyone, team members still benefit from being able to listen in.

Time is set aside each day to do some form of meditation or mindfulness exercise. This is not a group activity, but team members do this at the same time each day. By synchronising these activities, the opportunities for collaborative working are maximised. The effect of taking this time is really felt. Afterwards, team members are all very much more relaxed and able to focus.

As part of this transition, we hosted a number of webinars to share good practices for a team working fully remote. Most of the John Lewis & Partners teams that we work with were already set up to enable home working. However, moving from a few people occasionally working remotely to everyone working remotely all the time is not a trivial transition. Our webinars are designed for teams that are already comfortable with working remotely. We share tips and practices that will really help them gel and perform in a remote-first environment.

For example if you want to learn some of the techniques we use to build high-performing remote-first teams watch this webinar.

Part of our mission working with John Lewis & Partners is to enable their Partners. This means that our consultants transfer the necessary skills and knowledge to the Partners so they can continue to develop new digital services and products for their customers.

At Equal Experts, we have been building a remote-first mindset for years and have engaged in a number of fully remote deliveries. That’s why we published and open-sourced our remote delivery playbook earlier this year.