Our Thinking Tue 8th June, 2021

Is it Time to Rethink… “Data is the New Oil”?

In my opinion, ‘data is the new oil’ is a metaphor that should be used with caution, especially by those who wish to portray data in a positive light.

That is, whilst there are many similarities between data and oil, most are unflattering. I believe that by confronting these negative connotations, we can have the right conversations about our responsibilities in the Age of Data, whilst finding better metaphors to describe them.

A Brief History

In the beginning was Clive Humby, the British data scientist, who coined the phrase ‘data is the new oil’ back in 2006. It has since become part of the business and management lexicon, repeated by journalists, policy makers and world leaders alike. In common usage, the metaphor emphasises the fact that oil and data are critical parts of the modern global economy, with the latter gradually replacing the former. Humby also recognised that data, like oil, has no intrinsic value, and expensive processes of refinement have to be applied before they become valuable.

Certainly, data powers much of the economy, just as oil powers our engines. Much of what we do online is part of a Faustian pact, in which we allow the tech giants to harvest our data in exchange for useful, free tools such as email. Tech evangelists minimise the costs whilst emphasising the benefits of data in our lives. But if we ever stopped to actually consider how much personal information we give away each day we’d put our laptops in the freezer. And comparing data to oil has a dark side. Oil is a dirty business. Oil-based products – petrol, plastics, chemicals – are harming the planet. Put simply, this isn’t the kind of company data should want to keep.

Oil Spills and Data Leaks

Let’s look at one of the most regrettable similarities between data and oil.

As oil moves around the globe, leaks happen (there have been 466 large oil spills in the last 50 years). Much has been said and written about these disasters and the environmental damage they cause. Coupled with the growing apprehension of the role oil plays in the global climate crisis, you might expect the demand for oil to be falling like a stone. You’d be wrong.

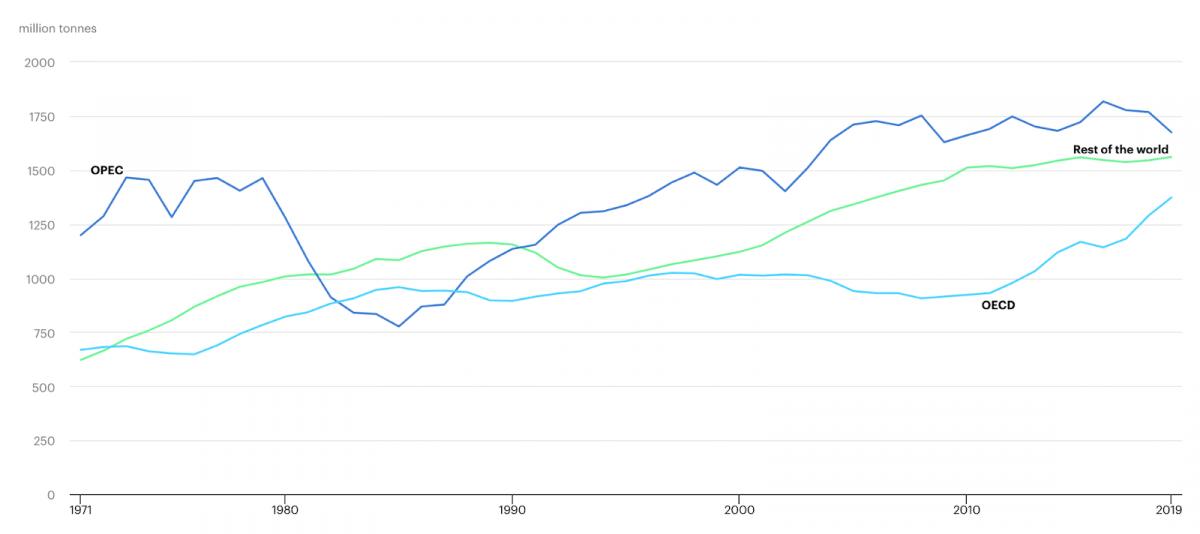

Figure 1: Global Oil Production 1999-2020

And if that graph surprises you, consider this:

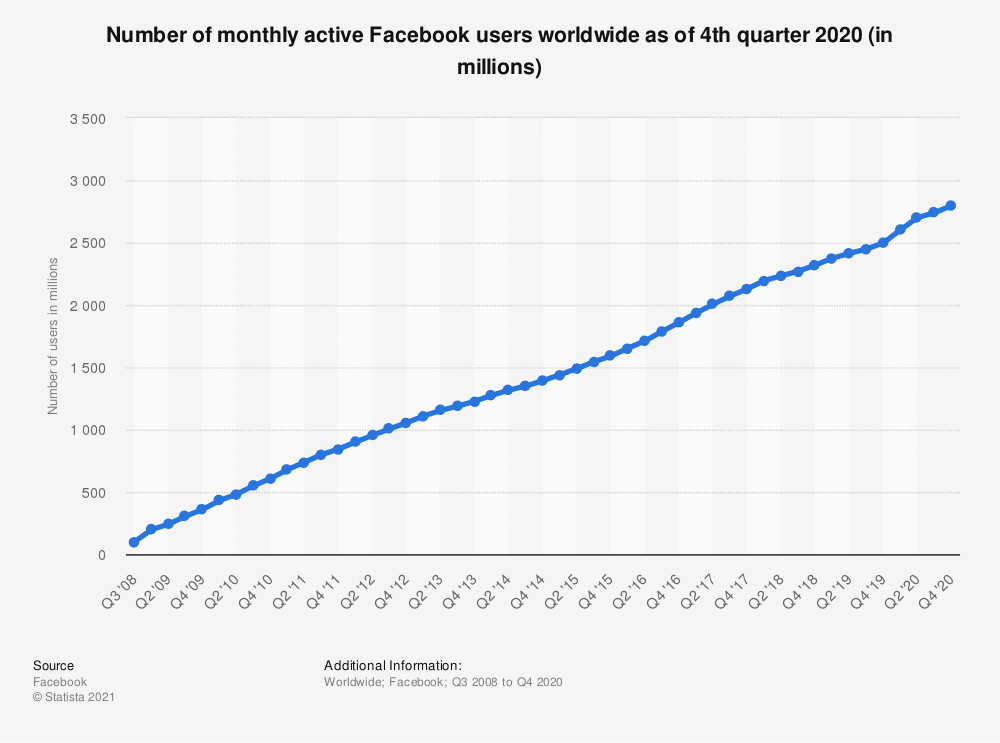

Figure 2: Number of monthly active Facebook users worldwide

If you’re looking for indicators of decline following Facebook’s equivalent to Exxon Valdez – the Cambridge Analytica scandal – you won’t find it. Lest we forget, Cambridge Analytica harvested upwards of 87 million Facebook users’ personal data without their consent, then sold that data to political consultancies. This dubious practice may well have affected the outcome of the 2016 US Presidential election, and the Brexit vote in the UK the same year. But despite #deletefacebook and some social and political huffing at the time, the scandal didn’t make a dent on Facebook’s fortunes.

So tech giants and oil barons are alike, in that they leak and pollute and behave with disregard for the wider community, without much consequence.

Oil and Water

The question then becomes, is there a better metaphor out there? During my research I’ve happened across plausible arguments in favour of a cataclysmic comparison – that is to say, data is the new nuclear power (awesomely powerful, yet capable of dreadful contamination and destruction). When discussing this piece with a leading practitioner, he reminded me that data ‘flows’ from one place to another, and suggested that it’s like water (it’s nourishing and necessary – but needs filtering and processing to be safe; it can leak), or slightly less appetisingly, data is like blood.

All are decent metaphors (I particularly like the ‘water’ alternative). However, water (like uranium, or blood) is physical – if I buy and drink a litre of water, no one else can drink that same litre – whereas data can be used simultaneously in different places, at multiple times in multiple ways. And data is unique, whereas one glass of water is essentially the same as any other.

If we stick with data being like oil, we’re left with harrowing images of sick seabirds and bleached reefs. Which prompts me to ask: are we in danger of losing something valuable, by tarring data with the same oily brush?

Data for Good

Last year, academics at the University of Oxford interrogated a massive dataset to assess the effectiveness of a range of potential treatments for Covid-19. Using advanced data science techniques, they discovered an unexpected pattern – namely, a drug used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis could save lives, reduce the need for a ventilator, and shorten patients’ stay in hospital. Such a breakthrough should be seen as an unalloyed success story for all those involved, whilst also containing within it some valuable lessons about how we treat data.

The most important, from my perspective, is that the data sets were held securely by NHS Digital, after full consent was granted by those involved. Not one item of data was taken without express permission, or used for any other purpose than that for which the data was originally sought. In other words, the data was willingly and knowingly given for a specific and transparent purpose. Safeguards were put in place, adhered to, and all parties acted responsibly throughout. Why can’t all data be used in this way?

Data Guardianship

Ultimately, the NHS Digital story, and others like it, reinforce the importance of the concept of ‘Data Guardianship’. That is, all actors in our data-rich economy need to take responsibility for minimising the damage their actions cause in the present, whilst making every reasonable effort to safeguard the future. The three pillars of Data Guardianship are:

- Organisations shouldn’t gather any data that might expose the subject to excessive privacy risks, now or in the future

- Data should not be hoarded ‘just in case’ – organisations should refuse to keep anything they don’t need

- Organisations should be proactive in explaining what data they’re collecting, how they intend to use it, and what rights the data subject has, in order to enable better decisions around consent

Ultimately, we have to make sure data doesn’t become the new oil, and instead find a metaphor that emphasises the positive values that underpin these pillars, instead of contradicting them. We can’t simply hope that some future phenomenon will make our data safe from abuse – we all need to educate ourselves, and then act accordingly, today. And if we can’t trust companies to behave responsibly, we shouldn’t give them our data in the first place.

Perhaps we should think of our data as a vote that we cast in support of those organisations that are behaving best in the data-based economy. In fact, maybe that’s the new metaphor I’ve been searching for all along: data is the new democracy.